We meet on every Sunday at 12-1:30pm PST/3-4:30pm EST/8-9:30pmUTC.

Sapphic Circle is a space for lesbians to come together for thoughtful discussions on a variety of topics. We seek to build lesbian community through engaging in lesbian ideas, politics, media, and more!

What Is A Boston Marriage?

A Boston marriage refers to a long-term, committed partnership between two financially independent women who lived together without male support. Some of these relationships were romantic; others were platonic. The practice took place primarily in New England beginning in the 1870s and died off in the 1920s.

The common narrative of the Boston marriage is often portrayed as a long-lasting cohabitation between two female academics in the era of the American Suffragette. A subtype known as a Wellesley Marriage, referring to Wellesley College, in Massachusetts also existed during the same time period. However, Boston marriages generally occurred between women who were financially independent through various means: widows, those from upper class families and professionals of various sorts.

While the concept came to prominence and was most commonly practiced and recorded in the United States, retrospectively, the earliest well-known instance of a Boston marriage is that of Lady Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby. They were Irish aristocrats who ran away together to Llangollen, Wales in 1778 and lived there together for fifty years. Their home became a common a popular destination for artists and writers in the UK at that time.

Late Victorian Origins

The rise of women’s colleges in the eastern United States took place in the mid-19th century. As increasing numbers of women were able to pursue higher education, they gained both the financial independence and the social networks that made Boston marriages possible.

The novel The Bostonians, by Henry James was published in 1886, is thought to have inspired the term Boston marriages, as it tells the story of two women who are intensely connected to each other. This fictional portrayal reflected real social practices, as documented in contemporary letters and diaries. The author’s sister was Alice James, whose relationship with Katherine Loring is very well documented. It is likely that the book was heavily based upon his sister and her social life.

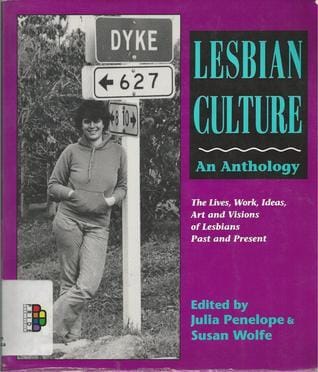

Lesbian historian Lillian Faderman has compiled many records of well known Boston marriages in her 1981 book, Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women from the Renaissance to the Present. There is a particular focus on the relationship between novelist Sarah Orne Jewett (1848-1892) and writer/philanthropist Annie Adams Fields (1834-1915), whose Boston marriage lasted almost thirty years.

For many years during that time the two women lived together a part of each year, separated for another part of the year so that they could devote complete attention to their work, traveled together frequently, shared interests in books and people, and provided each other with love and stability… (Faderman, 1981, p. 197).

Faderman’s account reveals the emotional and practical depth of these relationships. In the Victorian era, the devotion and commitment exemplified within Boston marriages was seen as pure, commensurate with gendered narratives at that time. In some cases, the letters between the women in question indicate a sexual relationship, and in other cases, indicate only a deep friendship. Regardless, because devotion between women was seen as virtuous, societal norms didn't prevent these women from committing themselves to each other.

Often, one of the most important aspects of these unions was finances; they wanted to make sure whatever income they had, remained under their control. Historical records suggest that these women carefully managed their finances to maintain independence; they never wanted to be subjected to the whims of a husband.

In her clever story about role re-versal, "Tom's Husband," Jewett showed heterosexual marriage to be destructive to women because they merge their identities in their husbands, lose interest in things outside the house, feel themselves growing rusty and behind the times, suspect their spouses can get along pretty well without them, regret having missed much of life, and generally believe they are failures. Jewett would have none of that in her own life. (Faderman, 1981, p. 198).

Given that these women were often suffragettes or New Women, it's sometimes hard to know whether political values, romance, or financial independence were the primary concerns that led women to make the choice to partner with each other.

Early 20th-Century Shifts

As the Edwardian era began, women carried on with their Boston marriages, but societal interpretations of them changed. The presumption of the pure and virtuous woman was crumbling, being replaced by a new, more insidious female archetype. Freud had popularized the notion that women were just as sexually deviant as men, if only you were paying close enough attention. The concept of the sexual invert, put forth by Havelock Ellis and John Addington Symonds was no longer confined to research, but was now making the rounds in popular culture.

Taken together, these cultural shifts meant that devotion between women was no longer read as innocent affection but instead as, at best, suspicious and, at worst, deviant. These women could now be pathologized and labeled as abnormal, despite no changes to their lifestyle.

It is noteworthy that when Annie Fields wanted to bring out a volume of Sarah Jewett's letters after Sarah's death, Howe, according to his daughter Helen, "laid a restraining editorial hand across her enthusiasm." He suggested that Annie omit four-fifths of the indications of affection between them "for the mere sake of the impression we want the book to make on readers who have no personal association with Miss Jewett... I doubt... whether you will like to have all sorts of people reading them wrong." Helen Howe says that her father was probably "distressed to have to recognize the sentimentality in Sarah." What probably distressed him, however, was what the two women's romantic friendship laid bare for the world to see: such a love was common and appropriate behavior in the century in which the two women had spent most of their lives (and he saw it himself as common and appropriate at that time); but it suddenly became "abnormal" in a twentieth-century context, although nothing about the nature of the relationship had changed (Faderman, 1981, p. 197).

What was once seen as virtuous companionship was now seen as suspicious intimacy. In the letters and diaries of women who were in Boston marriages, the generational shift is palpable. Younger women are self-aware and concerned about the perception of impropriety, while older women are not.

It probably would have astonished Jewett that Mark Howe saw anything to censor in her letters to Annie Fields. In the context of her time, her love for Annie was very fine. But Willa Cather, who was almost twenty-five years her junior and came of age in a different environment, knew that what Jewett's generation would have seen as admirable, hers would consider abnormal. There is absolutely no suggestion of same-sex love in Cather's fiction. Perhaps she felt the need to be more reticent about love between women than even some of her patently heterosexual contemporaries because she bore a burden of guilt for what came to be labeled perversion (Faderman, 1981, p. 201).

Chapter 4 Boston Marriage, from Lillian Faderman's 1981 book, Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women from the Renaissance to the Present is heavily referenced in this article. If you'd like to read the chapter in full, here is a PDF:

Reinterpretation and Academic Revival

The historical understanding of Boston marriages laid the groundwork for modern reinterpretations of same-sex and platonic partnerships. In the 1970s, researchers and academics were taking a look at the letters, diaries and published writings of women in Boston marriages. This is when the question of sexual rather than simply platonic love became much more prominent. One notable book is: The Ladies of Llangollen: A study in Romantic Friendship by Elizabeth Mavor (1979).

It was at this point that the term Boston marriage became almost a euphemism for lesbian marriage, in some lesbian subcultures. This interpretation is necessarily limited, reducing a complex social and economic survival strategy to a single dimension. In 1981, Lillian Faderman sums up some of her thoughts:

Whether these unions sometimes or often included sex we will never know, but we do know that these women spent their lives primarily with other women, they gave to other women the bulk of their energy and attention, and they formed powerful emotional ties with other women. If their personalities could be projected to our times, it is probable that they would see themselves as "women-identified-women," i.e., what we would call lesbians, regardless of the level of their sexual interests. (Faderman, 1981, p. 190).

Modern Context

The term Boston Marriage is not only used as historical reference. It is still used by some lesbians to describe a sexless lesbian partnership. In the Introduction to the 1993 book, Boston Marriages: Romantic But Asexual Relationships Among Contemporary Lesbians, editors by Esther D. Rothblum and Kathleen A. Brehony outline why and how they use it.

We decided to reclaim the term "Boston marriage" to describe the concept of romantic but asexual relationships between lesbians today. We were interested in describing lesbians who were couples in every way except that they were not currently sexually involved with each other (and might never have been sexually involved with each other) (Rothblum & Brehony, 1993, p. 5).

Much more recently, platonic, same-sex marriages are making a comeback. In 2021, Deirdre and Chiderah made headlines by publicly announcing that they were in a platonic marriage. The idea appealed to many feminists at the time, and recent changes to our economic and political environment have made it even more so.

‘We are each other’s person and we are soulmates, but obviously Chiderah is straight and I am gay, so we both have different needs we can’t fulfil for one another,’ Deidre explains. ‘So we both seek casual encounters outside of our marriage’ (Metro, 2021).

Anecdotally, the trend of platonic marriage among women is on the rise. While there is very little data, Elizabeth Pearson covered the phenomenon in 2024 for Forbes in her article, Platonic Marriages: Why Women Are Getting Hitched To Their Besties. It seems like as long as the institution of marriage is still around, women are going to try to use it in an effort to maintain our independence.

While this trend might seem unconventional, it aligns with a growing recognition that marriage is not solely about romantic love. It can also be a strategic partnership that enhances both parties' lives in meaningful ways.

By leveraging the legal and financial benefits of marriage, women can create stable, supportive environments that enhance their personal and professional lives. This trend not only challenges traditional notions of marriage but also opens up new possibilities for how we define family and partnership in a world where women long to feel more in control of their bodies and lives (Pearson, 2024).

Questions To Consider

- Have you heard of a Boston Marriage before? What did you think of the concept?

- Do you think it's true that these women would have likely described themselves as "woman-identified women"? (a woman who defines herself and her values in relation to other women, and not in reference to male-dominated social structures)

- Given how difficult it was to be financially independent as a woman in the era of the Boston Marriage, how do you think finances played into the decision making of these women? Keep in mind that until the 1960s in the US and much of the West, the marriage bar existed; women would be fired from their professional jobs if they married.

- Given that there were almost certainly asexual and sexual Boston marriages being practiced within the same community of women, do you have any thoughts on the potential issues that may have created?

- Explain why you think its a good or bad idea to look at historical concepts through either a historically informed lens or a modern lens.

- Does it make sense to you, for some women to reclaiming the term Boston Marriage, as a descriptor of a sexless lesbian relationship?

- What potential is there for the new Platonic Marriage? Do you think it's a good or bad idea?

References

Faderman, L. (1981). Surpassing the love of men: Romantic friendship and love between women from the Renaissance to the present. William Morrow. (Chapter 4: “Boston Marriage,” pp. 190–203.)

Rothblum, E. D., & Brehony, K. A. (1993). Introduction: Why focus on romantic but asexual relationships among lesbians? In E. D. Rothblum & K. A. Brehony (Eds.), Boston marriages: Romantic but asexual relationships among contemporary lesbians (p. 5). University of Massachusetts Press.

Metro. (2021, April 16). Platonic best friends get married as their connection beats romance.

Pearson, E. (2024). Platonic marriages: Why women are getting hitched to their besties. Forbes.

FAQs & Code of Participation

If you have questions, please read over Sapphic Circle's Frequently Asked Questions and review our Feminist Code Of Participation.