Reading Circle meets every Monday at 4pm PST/7pm EST/12am UTC.

Reading Circle is a space for women to explore feminist literature as a group. Every week, we will read a short essay or excerpt of writing about feminist theory or women’s herstory, then discuss. Please read or listen to the text before each session, so we come together for a thoughtful discussion!

About The Author

Judy Brady wrote this in 1970, originally as a speech that she gave at the Women's Strike for Equality on August 26, 1970, in San Francisco. It draws heavily on her own life experience; she discontinued her education after she was advised that she was unlikely to be hired in academia, despite her skill and aspiration. She went on to be a housewife and mother, while her husband worked as a professor at San Francisco State University.

It's notable that this was written under her maiden name, and much of her activism was done under that name; her married name was Judy Brady Syfers. The year before she gave this speech, she opened up her home to protesting faculty and students from her husband's university, where she helped organize and feed them. When the five month strike ended, her husband was thanked for supporting the strike but she was left out.

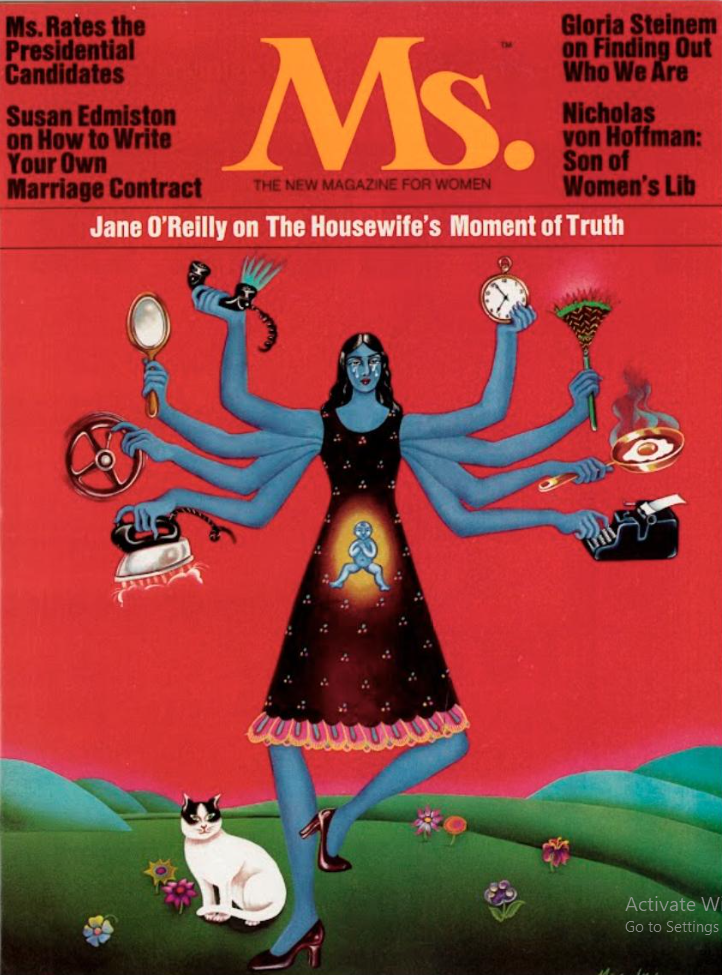

This short and powerful feminist speech was first published in Tooth and Nail, which later became Motherlode, where Judy Brady worked. It's most well known publication is probably in Ms. Magazine. It was in the the December 20-27th, 1971 issue of Ms. Magazine, a preview insert inside New York Magazine. The first standalone issue of Ms. Magazine later came out in July 1972, which also contained this speech.

Recording

You can listen to a recording of this week's reading here.

Text

You can read this weeks text by following this link.

You can also download a PDF version here:

Key Concepts

Reproductive Labour

A broad debate on reproductive labour was firstly brought up by the feminists who initiated the campaign wages for housework in the early 1970s (amongst others by Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James). In lieu of a real policy proposal they rather aimed at pointing to the fact that female housework was firstly unpaid and secondly a necessary condition for the capitalist production process. They, furthermore, emphasized that reproductive activities are also labour which is characterized by gender hierarchy and not a goodwill gesture by women.

...

Reproductive labour comprises remunerated as well as unpaid activities that reproduce the work force - this includes daily activities as cooking, washing clothes but also bearing children. The term reproductive labour emphasizes the role of those activities within the production process, namely the reproduction of the work-force. Throughout the past years, the debate on those activities mainly carried out by women shifted from reproductive activities to the term “care” - the latter focuses on the type of the activities, the work with and the caring for persons, which is devoted to the well-being of others and also includes the caring for elderly people. (Exploring Economics Team, 2016).

Wages for Housework

The New York Wages for Housework committee, meanwhile, seemed to take a more confrontational approach. In her book Callaci quotes from its 1974 declaration, which she bought as a poster to hang at home: “The women of the world are serving notice! We want wages for every dirty toilet, every indecent assault, every painful childbirth, every cup of coffee and every smile. And if we don’t get what we want, we will simply refuse to work any longer!” What leaps out is the phrase “indecent assault”, as if that were just part of the 70s housewife’s lot, along with scrubbing toilets, and something for which she should be compensated. The second line of Federici’s manifesto – “They call it frigidity; we call it absenteeism” – certainly suggests she saw marital sex as work, and consent as uncomfortably linked to financial dependency. (Hinsliff, 2025).

The Second Shift

The realization of the second shift came about not long after women started working outside the home, but the term was not officially coined until 1989 when Hochschild published her book, The Second Shift (1989). There are many varying definitions of the second shift, but the most common definition is that the second shift is the dual burden of paid and unpaid work experienced by working women (Hochschild, 1989).

From 1950 to 1986 the amount of women in the workforce increased by 25%, from 30% to 55%, respectively (Hochschild 1989). When The Second Shift (Hochschild 1989) was published, dual-earner households made up nearly 60% of all married couples with children. The amount of work required of a dual-earner household increases exponentially once a child is brought into the family (Sayer et al. 2009). While the second shift affects all working women, it is especially apparent for mothers, particularly those with preschool age children (Hochschild 1989; Mattingly and Bianchi 2003; Milkie et al. 2009; Sayer et al.2009). (Van Gorp, 2013).

Reading Questions

- What pops out at you about the first phrase of this essay, and how it sets the tone for what follows? "I belong to that classification of people known as wives. I am A Wife. And, not altogether incidentally, I am a mother."

- What do you think the word "wife" evokes in men? In women? In feminists? What are your personal feelings about the term "wife"?

- The author speaks about how she would like to hypothetically become economically independent, but that this would rely on the unpaid work of a "wife". What are your thoughts about the economic dependence or independence of women, married to or partnered, with men?

- It's taken as a given that "the wife" will have to cut back on her personal time, work, education, etc. to prioritize childcare at all times, but the husband never will. Do you think things have changed much on this issue since 1970?

- Do you think that single women or married women today, have the same attitude or a different attitude, towards housework, than what is laid out by the author?

- Where do sex based stereotypes and weaponized incompetence come in to play, in the distribution of housework and child rearing, in the nuclear family?

- Do you think the burden of the mental load associated with the social labour of organizing and maintaining family and community relationships, has shifted between the sexes, in the last 50 years?

- What do you think of the author's description of the sexual expectations put on "the wife" in the context of financial dependence?

- How would you describe the expectations of contemporary heterosexual partnerships, with regards to sexual behaviour? Is it markedly different than this description from 1970?

- Now that we are in an era where many women are choosing to partner with men, without marrying, do you think men's attitudes towards "replacing" their female partners, when the whim takes them, are different?

- How much of what the author describes in this essay, would you personally categorize as abuse? (emotional, sexual, reproductive, financial, etc.)

- Even if one could argue quite confidently that some of what is described here is abuse, how do entrenched sexist stereotypes play a role in the normalization of those behaviours or dynamics?

References

Brady, J. (1971, December 20–27). I want a wife. Ms. Magazine.

Exploring Economics Team. (2016). Reproductive labour and care. In Exploring Economics.

Van Gorp, K. (2013). The second shift: Why it is diminishing but still an issue. The Review: A Journal of Undergraduate Student Research, 14, 31–37.

Code of Participation

If you have questions, please read and review our Feminist Code Of Participation.